David Altmejd Prélude pour un nouvel ordre mondial

In Prélude pour un nouvel ordre mondial, Canadian artist David Altmejd unveils a body of new sculptures and drawings. For the first time in his career, Altmejd combines these two mediums, exploring their connections and revealing how past and new ideas in his work come together. As the title implies, this exhibition marks the beginning of fresh trajectories in Altmejd’s ever-evolving artistic realm.

From the celestial heavens to the depths of the earth, the natural world is the lifeblood of David Altmejd’s oeuvre. In his new sculptures, Altmejd introduces an expanded pantheon of hybrid, anthropomorphic beings that allude to the multi- faceted power of animals in various cultures and belief systems. The works are rich in symbolism and evoke a transcendent quality that surpasses the boundaries of the physical world. Rams, an orca, snakes, a panther, birds, rabbits and swans have all made their way into the oeuvre, serving as metaphors and companions since time immemorial, with their wisdom often pointing the way to spiritual enlightenment. Consider, for instance, the Bible, the Koran, the Dhammapada, the Analects of Confucius, or Aesop’s fables.

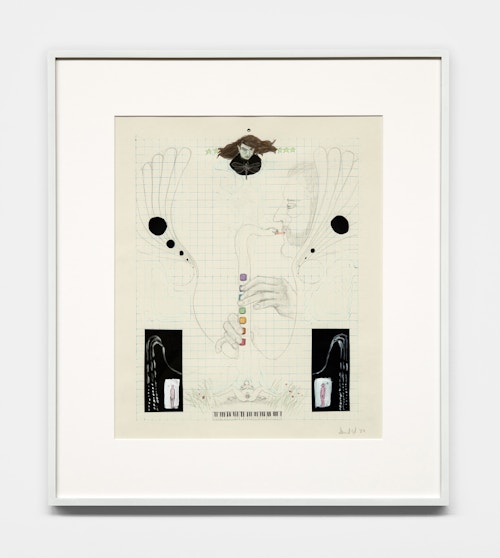

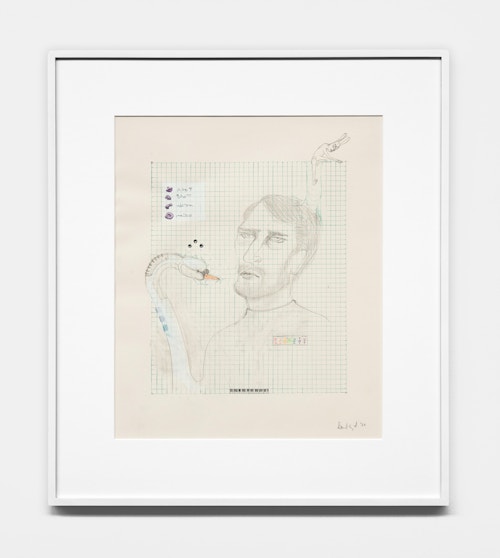

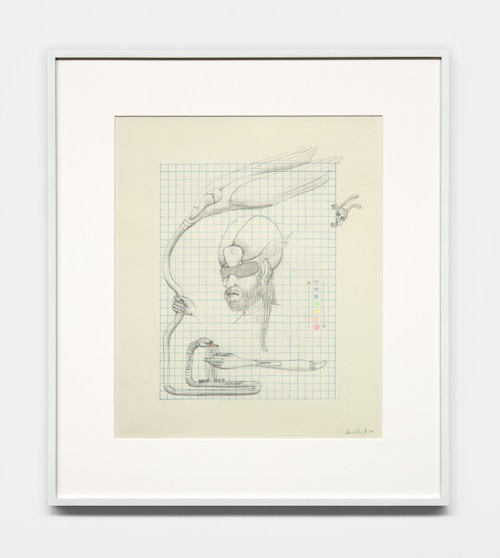

Among the variety of animals Altmejd explores, swans take centre stage in his new body of work. The swans have metamorphosised into musical instruments, through which the artist draws parallels between nature and music, highlighting their shared qualities of order and disorder. The seven colours of the instrument’s keys here are not coincidental, symbolising various references across different eras and cultures¹. In numerology, seven represents the union of the spiritual (3) and material (4) worlds, while in music, there are seven notes in a musical scale. Conversely, the figures playing swan instruments wear helmets that conceal their vision, suggesting a sense of detachment from their surroundings. The idea that they might hail from another dimension is further supported by the presence of space-time grids in the artist’s drawings. It is also worth noting that, human eyes— which Altmejd once emphasised or even replicated—have now vanished, along with any reference to the artist himself. In these new works, the focus moves from self- portraiture to visored beings.

Altmejd’s fused forms evoke metamorphosis, growth and decay, and often visualise transformation processes. Animals and humans frequently mutate, as in Nocturne no 1, where human hands mould the whale’s flesh, a creature that features in many ancient mythologies. The unctuous, carbon-like matter of the body is akin to the prima materia, which is the primitive formless base of all matter, similar to chaos, the quintessence or aether. This sculpture seems to embody the regenerative force of nature, with a cosmic egg embedded in its back and a diamond–carbon in a different state–illuminating the world. It can be read as a metaphor for the splendour and enigma of the cosmos. Other enigmatic beings emerge, like the figure Ève, with its shimmering and venomous green face, evocative of witches, ogres, goblins and trolls. This green also resembles the iridescent colour of scarab beetles, revered in Ancient Egypt—creatures that also find their way into the artist’s drawings. Blending reality and imagination, Altmejd often employs myths and legends to explore nature. These allusions tap into ancient human perceptions of nature as a powerful and unpredictable force.

The intertwining of humans and animals also echoes the ideas of the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875-1961), who held that animals are exalted beings, or the ‘sacred’ part of a person’s mind. He believed that they were much closer to a secret, natural order than humans, and thus nearer to the ‘absolute knowledge’ of the unconscious. Unlike people, who are bound by moral constructs of good and evil, animals adhere to natural laws, which Jung considered a form of superiority. He explored how our ‘animal nature’ could serve as a psychic source of renewal and wholeness.

These themes are reflected in the artist’s mixed-media drawings, which are neither preparatory studies nor working sketches. The matrixes reference space-time grid distortions and the theory of special relativity, while also invoking, in another sense, the transfer techniques of classical sculpture. But by virtue of being hand- drawn, the grids are imperfect. At times, they are punctured, caught in a vortex or distorted, creating glitches in the space-time continuum. The images in the drawings are fantastical and uncanny, arcane and vivid. Cryptic, undecipherable symbols represent the ‘language of the unconscious’.

Altmejd’s work, through its synthesis of seemingly opposing elements, reveals a deep interconnectedness between nature and the human form, life and death. The tension between organic and synthetic forms creates a dynamic that blurs the line between nature and artifice, evoking a sense of “unsettling familiarity”—a haunting blend of the known and unknown. In this paradoxical realm, the ordinary world is transformed, inviting us to reconsider our perceptions of reality.

David Altmejd (b. 1974, Montreal, Canada) lives and works in Los Angeles. His work was the subject of a major survey exhibition entitled Flux at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France which travelled to the MUDAM in Luxembourg and the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal, Canada (2014-15). In 2007, he represented Canada at the 57th Venice Biennale. Public collections include Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Long Museum, Shanghai; and MUDAM, Luxembourg, among others.