Nathanaëlle Herbelin And there is a place you will not be able to return to

Nathanaëlle Herbelin’s second exhibition at the gallery presents a new series of portraits and interiors that navigate the fragile balance between immediate, everyday experience and the weight of an unsettled world. At once intimate and expansive, these paintings reflect a desire to hold on to moments of connection―small yet significant interactions with friends, neighbours, and family―amidst an undercurrent of grief, uncertainty, and shifting realities. Herbelin’s approach is neither sentimental nor detached; rather, she paints with an acute awareness of how personal and collective histories intertwine. The act of painting becomes a way to ground herself, to acknowledge absence, and to bear witness to both quiet rituals and emotional thresholds.

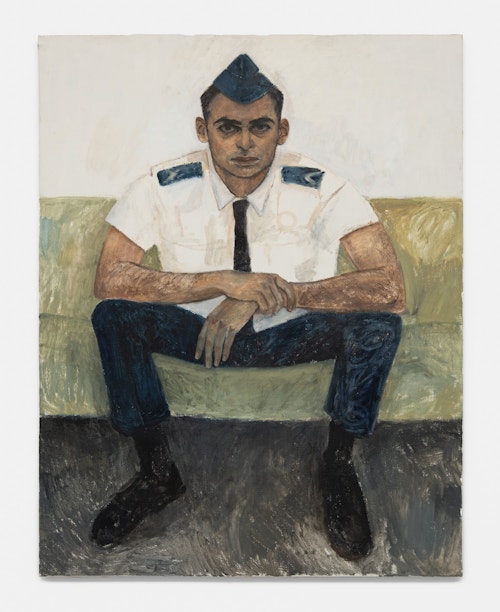

While Herbelin’s earlier works were characterised by vibrant colours and clearly defined settings, the paintings in this exhibition embrace ambiguity. Figures emerge from undefined or weighty backgrounds, emphasising presence over place, memory over setting. Arie, the artist’s late grandfather from Israel, is painted posthumously from photographs. His depiction resists traditional hierarchies of representation—someone who might not typically be immortalised on canvas is here granted a quiet yet steadfast visibility. Herbelin’s gaze is both tender and unflinchingly honest, stripping away embellishment to reveal the raw intimacy of her subjects.

The absent presence of Herbelin’s late grandfather can also be felt in two of Herbelin’s works depicting Jewish mourning rituals. In Shiva, Herbelin reconstructs, from memory, a bird’s-eye view of her grandfather’s home during shiva, the seven-day mourning period following a funeral. The painting reflects the charged atmosphere of this ritual, in which the bereaved remain at home, marking their loss through time-honoured rituals: sitting on low chairs, covering mirrors, and lighting a candle in remembrance. The second, larger work on this theme, Dîner aux œufs durs [Dinner with Hard-Boiled Eggs], interprets the Se’udat Havra’ah, the meal of condolence that follows a burial. Hard-boiled eggs―along with bagels, lentils and other round foods―are central to this meal, symbolising the cycle of life and renewal. The composition of the painting takes inspiration from Egon Schiele’s Die Freunde (Tafelrunde), groß [The Friends (Round Table), Large], 1918. Just as Schiele painted his own circle of friends gathered around the table, Herbelin populates Dîner aux œufs durs with her own acquaintances as well as imagined figures.

While portraits remain central to Herbelin’s practice, her nuanced depictions of interior spaces are equally poignant in conveying mood and atmosphere, revealing the psychological depths of her subjects. Two interior scenes, in particular, evoke contrasting realities and psychological spaces: one depicting a desolate kitchen, Ustensiles, and the other, Jérémie qui donne le biberon, portraying the artist’s partner, Jérémie, feeding their baby in a hotel room in China where the artist recently completed a residency. The panoramic view framed by the window in the latter painting contrasts starkly with the small, barely visible window in the kitchen, a subtle indicator of confinement and diminished hope. Similarly, the personal possessions on the hotel table stand in contrast to their near-total absence in the kitchen, despite other clues suggesting a recent human presence. The latter painting holds the quiet act of care in tension with the busy, impersonal cityscape beyond, reflecting the contrast between private tenderness and the vastness of the outside world.

The interplay between interior and exterior spaces―both literal and psychological―in this new body of work mirrors the artist’s negotiation of past and present, presence and absence. Whether reconstructing her grandfather’s apartment from memory, capturing the transient intimacy of a shared meal, or painting figures from her neighbourhood, Herbelin’s works resist easy narratives. Instead, her paintings offer a space where the everyday and the existential coexist, where the act of looking itself becomes an act of recognition.

- The exhibition title comes from the poem Eyes Sadness and Journey Descriptions (עצבות עיניים ותיאורי מסע), from the book Behind All This, Hides Great Happiness (מאחורי כל זה מסתתר אושר גדול) by Yehuda Amichai.

Nathanaëlle Herbelin (b. 1989, Tel Aviv, Israel) obtained a Master of Fine Arts degree from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2016, during which time she was invited to participate in an exchange programme at The Cooper Union, New York. Herbelin’s first solo exhibition in Asia, Feel the pulse, opens at the He Art Museum in Shunde, China (8 March to 8 June 2025). It will showcase the works made during her residency at the museum in 2024. Recent solo exhibitions include Être ici est une splendeur, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (2024); À la surface, le fond de l’oeil, French Institute of Tel Aviv (2022); Et peut-être que ces choses n’ont jamais eu lieu, Umm Al Fahem Palestinian Art Center (2021), Devenire Peinture, Yishu 8 prize, George V Art Centre, Beijing (2021); and group exhibitions such as the FRAC Champagne-Ardenne (2021); Passerelle Art Center, Brest (2020); the museums of the Abbaye Sainte-Croix (Sables d’Olonnes, 2019); Bétonsalon, Paris (2019); the Beaux-Arts Museum of Rennes (2018), Collection Lambert, Avignon (2017) and Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard, Paris (2017).