Sherrie Levine

Xavier Hufkens is pleased to present its inaugural exhibition with the influential American artist Sherrie Levine. As one of the artists who are most often cited in relation to appropriation art, it has to be recognized this category is too narrow to contain all that Levine’s work achieves. The more it is looked at, the more depth and complexity her practice yields.

Sherrie Levine is adept at making bodies of work that are both precise and confounding. Her reiterations of artefacts obtain their own aura — through a poised selection, of source artefacts, material, execution, and a stilled dramaturgy of sequence and presentation. These aspects still do not explain the mystique Levine’s work propagates: the magic seems to lie in the way the works relate, to each other, their earlier selves in whose image they were remade, Levine’s practice, and as physical markers to the vast networks of objects and meanings that comprise our collective cultural experience.

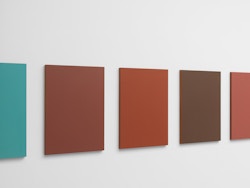

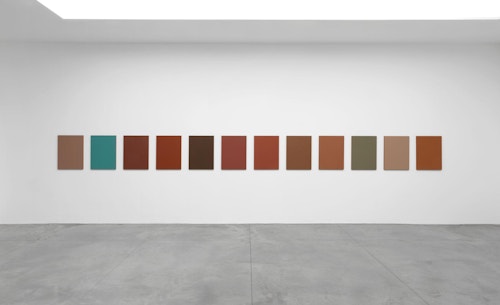

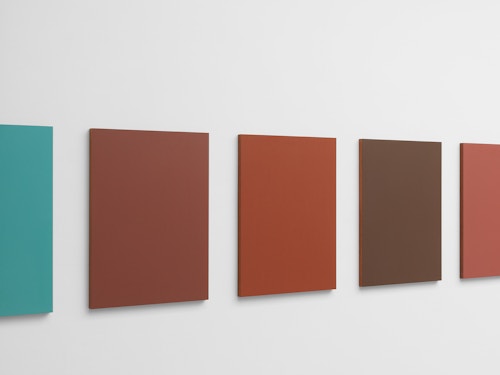

In the first room, Levine presents Monochromes After Emil Nolde: 1–12. The colours are distilled from the pixilation of a photograph of a painting of poppies by the German expressionist Emil Nolde (1867–1956). Levine’s choice of source is hardly innocent: in the nineteen forties Nolde was persecuted by the Nazis and forbidden to paint. He called the watercolours of flowers he made in secret during this period Unpaintings, a title which, by extension, also questions the status of these new paintings. We see a small bronze coffin, cast from a wooden original, polished to perfection, the carpentry details clearly visible. Tight Coffin brings to mind Dali’s obsession with Millet’s painting The Angelus (1857–1859). The surrealist sensed there was a child’s coffin at the feet of the workers in the field who had paused to pray, even if none was visible. In 1932-5 Salvador Dali wrote about his visions at length in his book The Tragic Myth of Millet’s Angelus: Paranoiac-Critical Interpretation. An x-ray confirmed his intuition in 1963. Sherrie Levine’s Tight Coffin is similar in shape and scale to the one unveiled in Millet’s painting. The object is like a Pandora’s box, suggesting a life unlived, and a locked-in charge capable of unleashing countless associations.

Levine’s Very Large Cradle relates to a painting by Van Gogh that Levine reproduced in an earlier work: a woman is pictured holding the strings that rock a cradle, which is left outside of the image. Van Gogh was influenced by Millet: the cradle and coffin touch on how ideas and forms reappear in the arts through time. Seeing them together further amplifies their associative potential.

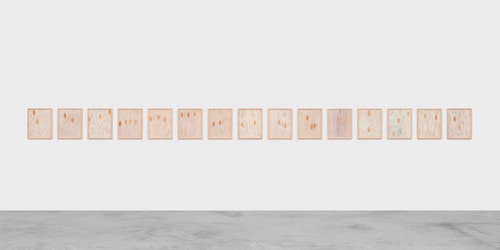

White Moonlight After Man Ray: 1–15, is one of a series of ‘knot paintings’ or ‘not-paintings’ Sherrie Levine began making in 1985. Taking plywood panels, the artist highlights the knots in the grain of the wood by painting them. The series is subtly varied, in terms of ground colour, and number and colour of the spots. The title of this particular work acknowledges a collage Man Ray made in which the grain of a blackened piece of wood suggested the clouds of a moonlit sky.

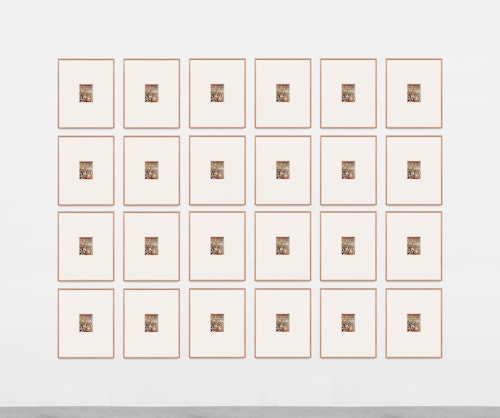

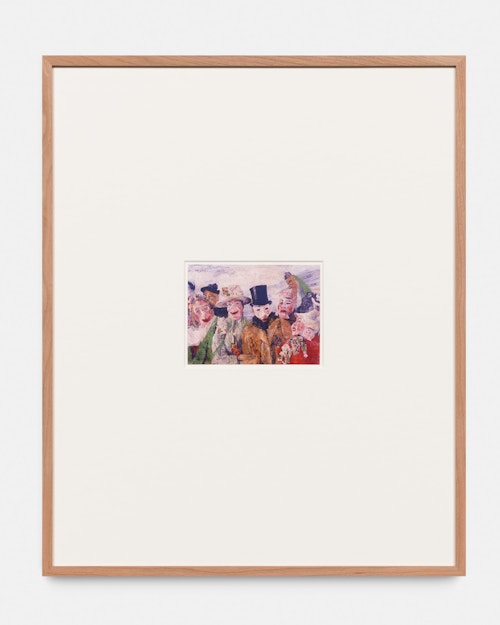

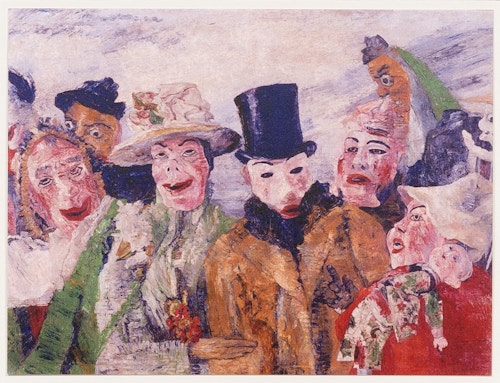

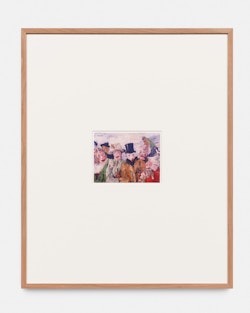

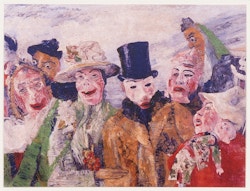

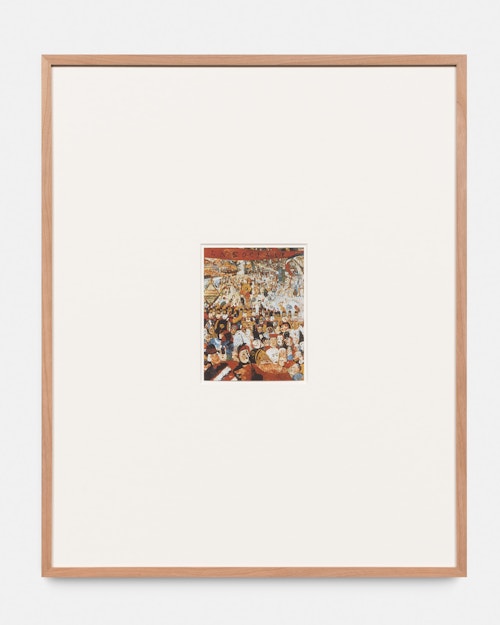

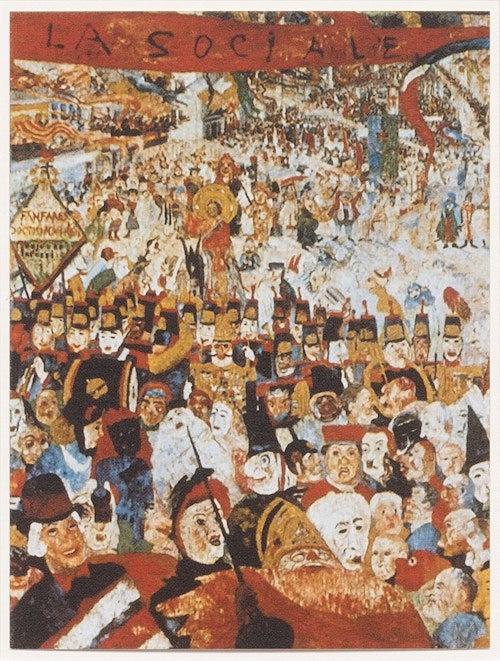

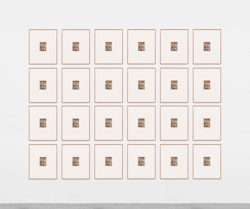

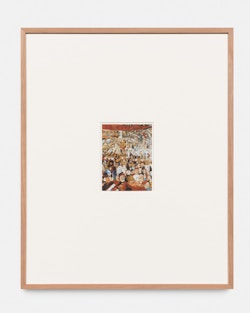

Two postcard collages of each 24 identical, framed postcards, manifest in and of themselves notions of repetition and seriality. And as we walk past them, we see every postcard differently, as the others crowd into our peripheral vision. The postcard of the first After Ensor: The Intrigue (detail) shows many people wearing masks, a recurrent motif of disguise in Levine’s work. They feature again in the second postcard collage that presents a detail of James Ensor’s painting Christ’s Entry into Brussels (1889). In this painting, the Anglo-Belgian artist depicted himself as Christ at the centre of a carnivalesque multitude.

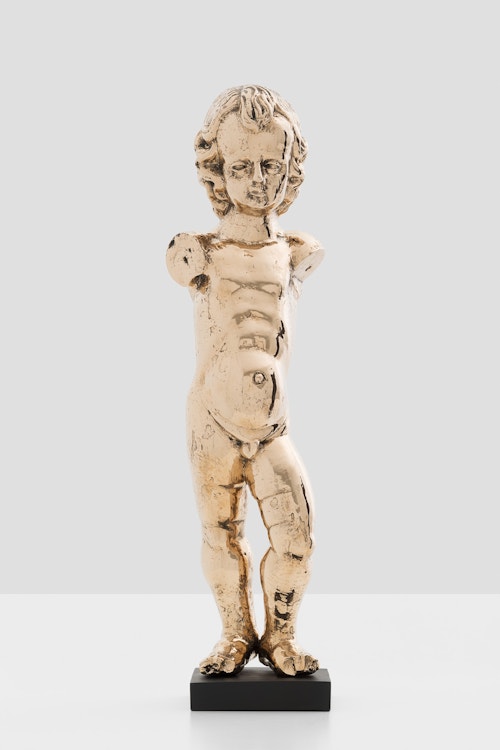

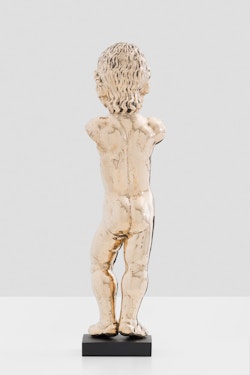

The viewer may imagine a further link to Brussels in the bronze Christ Child, a figure not unlike Manneken Pis, the fountain of a small boy that splashes forth in the centre of Brussels. This in turn harks back to Levine’s Fountain (Buddha), with which she reiterated Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 urinal/readymade Fountain that he signed R. Mutt. Taking a slightly different model by the same company in the same year, Levine’s Fountain (Buddha) bore no signature. It was executed in polished bronze — this quality recalled the sculptures of two other male, modernist artists, Brancusi and Arp — and has been Levine’s material of choice for casting ever since. Her sources are often rich in cultural references, but the way she reiterates and displays them are just as central to her project.

Medicine Ball harks back to Levine’s own Beach Ball, after Roy Lichtenstein’s Girl with Ball, an image he had found in a hotel advertisement. The sculpture was a contradiction-in-form, representing an object of lightness in bronze. This opposition is reversed again in Medicine Ball — the original item is already heavy. Lightness abounds once more in Rabbit, cast from a found folkloric item. It recalls Levine’s postcard collage After Dürer: 1–18, only here the motif is leaping.

The bronze Chemin Wild Boar emphasizes this stream of cultural associations Sherrie Levine’s works — together — seem to unleash. A wild boar may be small in size, but it can be strong and fierce, and capable of wreaking havoc and devastation. In Greek mythology, the animal is related to notions of fecundity and reproduction. In light of Sherrie Levine’s practice, which forever questions ideas of originality and copies of images and objects, the boar can be seen as a potent emblem of cultural fertility on overdrive.

Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) lives and works in New York. Her earliest work was included in the seminal exhibition Pictures (1977) at Artists Space in New York. In 1981 Levine debuted her controversial series Untitled, After Walker Evans which, together with other similar series, made her a leading member of the ‘Pictures Generation’, a group of artists using appropriation techniques to challenge the notions of authenticity and originality in the media-saturated 1980s. Levine’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at prominent institutions worldwide and can be found in major international museum collections.